Neural Network Accelerators (2024)

Introduction

Artificial general intelligence (AGI) Google’s Deep Mind characterizes current general AIs as emerging AGI. Level 1. Examples, their researchers say, include: ChatGPT, Bard, Llama 2, and Gemini 1. is speculated to arrive within only a couple of years from now. And with its emergence comes a plethora of issues. In these notes, I want to focus not on the consequences of AGI, nor what algorithms and software will lead to it, but rather the bottlenecks and problems there are especially regarding its hardware.

“We may recall that the first steam engine had less than 0.1% efficiency and it took 200 years (1780 to 1980) to develop steam engines that reached biological efficiency.”

writes Ruch et al. in 20112. Initial utility is typically achieved through effectiveness. We build something that gets the job done. And we do not mind how long it takes or how much it costs as long as it fixes the problem we couldn’t otherwise solve. We saw and see the same thing happening with the rise of the digital computer and now with modern AI based on artificial neural networks. CPUs and GPUs are general tools. Architectures meant to accomplish whatever task we throw at it. And time is the enemy of any technology company. Accelerate or be out-competed. Companies are willing to spend millions to innovate and train giant neural networks and billions to build the required infrastructure just to stay in the game. Efficiency is or has been an afterthought. But it is essential for making technologies widely available and allow for future technologies to build upon it!

Speed of computing as dependent on the consumed power for different hardware architectures: GPUs, digital ASICs, mixed signal ASICs, and FPGAs. I adapted and animated this figure based on a figure I found and saved quite some time ago 3.

Speed of computing as dependent on the consumed power for different hardware architectures: GPUs, digital ASICs, mixed signal ASICs, and FPGAs. I adapted and animated this figure based on a figure I found and saved quite some time ago 3.

In 2020-2023, the bottleneck for AI was arguably the amount of hardware available due to a global chip shortage so vast it made history45. In 2024, managing the voltage conversion is still a major issue for scaling up6. Voltage transformers play a crucial role in transmitting electrical power over long distances. To achieve this, voltage is stepped up for transmission and stepped down for safe use in homes, offices, and data centers. These transformers are bulky and expensive but necessary for safety and equipment protection. Demand for both types of transformers has surged since 2020 due to the needs of AI startups, data centers, and renewable energy sources like solar and wind farms789. A topic worth its own article. With these things hopefully more or more under control the future bottleneck will simply be the availability and cost of energy. In the short term, this means: how can we get the required energy cheapely? But as we continue to scale it also means: How can we make our hardware more energy efficient? How do we get to the top left quadrant of this figure? How do we achieve high performance for low power? Software optimization does not cut it. The hardware is too general to be efficient. And among other things the von-Neumann bottleneck10 fundamentally limits what these computers can do. There is of course also a data problem. Our algorithms are still not good enough to generalize from as little data as humans do. And books don’t contain as much as one might expect though it is of a high quality. The internet is far larger though. So then we may look at videos and podcasts etc. But will it be enough? Grog3 will require 100.000 H100s to train coherently. And at that point, there really is a lack of avaiable data, including text, video, and synthetic data. Much more is needed to satisfy the training needs of such large models. Read11 to learn more about how much training data is out there.

AI software has become seriously awesome and…

“People who are really serious about software should make their own hardware.” Alan Kay12.

Compute

“The base metric is becoming compute. Not money.” Harrison Kinsley (aka Sentdex)13.

This statement has been repeated over and over by engineers and technologists in and outside of Silicon Valley, including Sam Altman saying

“I think compute is going to be the currency of the future. I think it’ll be maybe the most precious commodity in the world.”14

“Compute” or computing power is simply a general term to describe how much computations can be done in practice to solve our problems or, simplified even further, it is a measure of how powerful a computer is15. Today’s GPUs reach several TFLOPs (Tera-FLOP) with a FLOP being a “floating point operation”. It has to be considered though that these can be 64-, 32-, 16-, 8-, or even just 4-bit operations! Nonetheless, 1 TFLOP = \(1\cdot10^{12}\) FLOP. The question is now how many operations can be done per second. The scaling hypothesis in AI posits that as the amount of data and computational resources available for training a machine learning model increases, the performance of the model also improves, often in a predictable manner. This hypothesis suggests that many AI tasks, particularly those related to deep learning, benefit from scaling up both the size of the dataset used for training and the computational power available for training the model. In practice, this means that larger neural networks trained on more extensive datasets tend to achieve better performance, such as higher accuracy or improved generalization, compared to smaller models trained on smaller datasets. The scaling hypothesis has been supported by empirical evidence in various domains, particularly in natural language processing, computer vision, and other areas where deep learning techniques are prevalent161718.

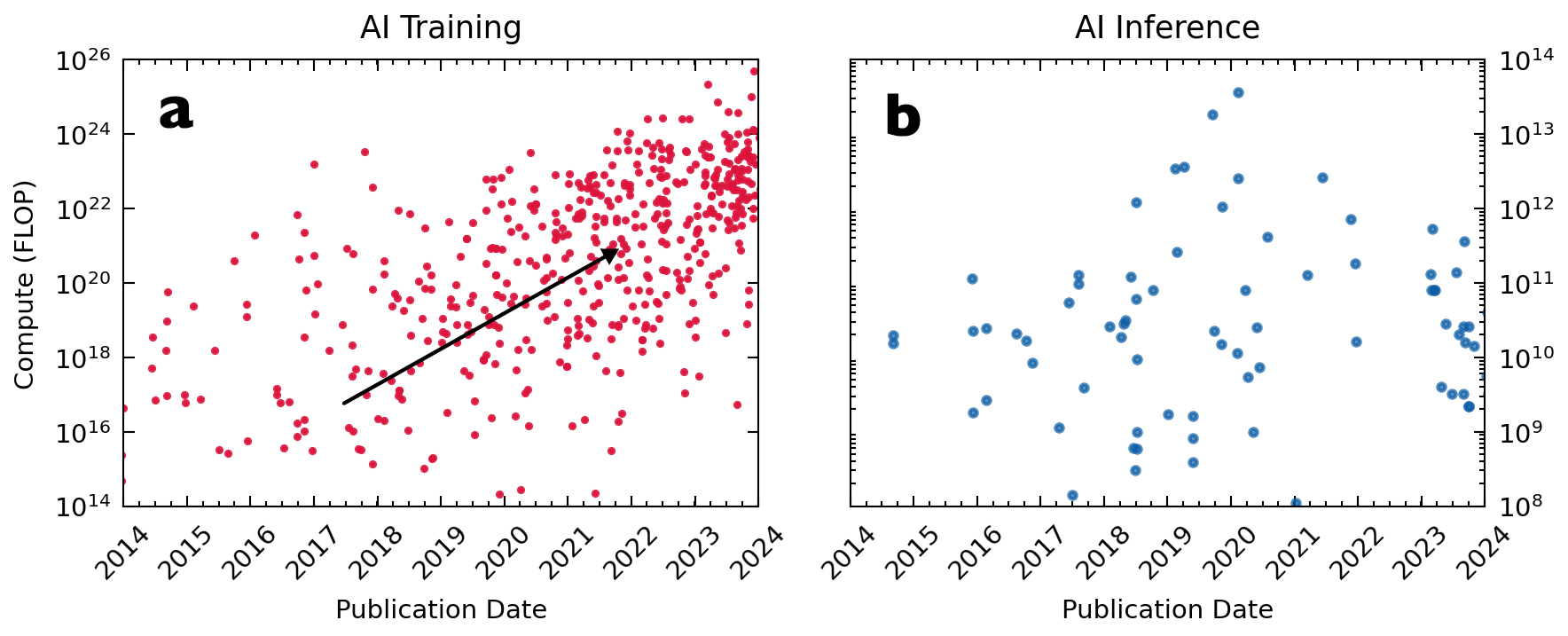

The amount of compute required to train (a) neural network and do inference (b) after training.

This figure was created by myself but the data was compiled by Jaime Sevilla et al.1920.

The amount of compute required to train (a) neural network and do inference (b) after training.

This figure was created by myself but the data was compiled by Jaime Sevilla et al.1920.

“Extrapolating the spectacular performance of GPT-3 into the future suggests that the answer to life, the universe and everything is just 4.398 trillion parameters.” Geoffrey Hinton21.

Training

Subplot (a) of the figure presented above shows the insane increase in training compute over time to create more and more capable AIs, rising orders of magnitude within years.

“[…] since 2012, the amount of compute used in the largest AI training runs has been increasing exponentially with a 3.4-month doubling time (by comparison, Moore’s Law had a 2-year doubling period). Since 2012, this metric has grown by more than 300,000x (a 2-year doubling period would yield only a 7x increase).” This was previously observed by OpenAI22.

As we can see in the figure above, this is not only true for the largest AIs but for AI in general!

Inference

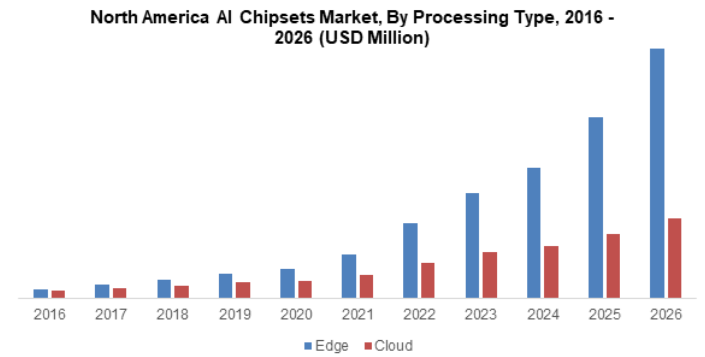

In fact, the North American AI chipset market is growing much faster for edge compute (which is essentially infernce) compared to cloud compute (mostly training) 23.

In a live stream, George Hotz mockingly said:

“All those fucks are trying to make edge AI. […] Look! The AI inference market is bigger than the AI training market! So we should all go for the inference market! It’s way easier! […] Easier and bigger! […] There are a hundred little fucks who make inference chips that no one really wants and only one who is making training chips (NVIDIA).” 24

In a live stream, George Hotz mockingly said:

“All those fucks are trying to make edge AI. […] Look! The AI inference market is bigger than the AI training market! So we should all go for the inference market! It’s way easier! […] Easier and bigger! […] There are a hundred little fucks who make inference chips that no one really wants and only one who is making training chips (NVIDIA).” 24

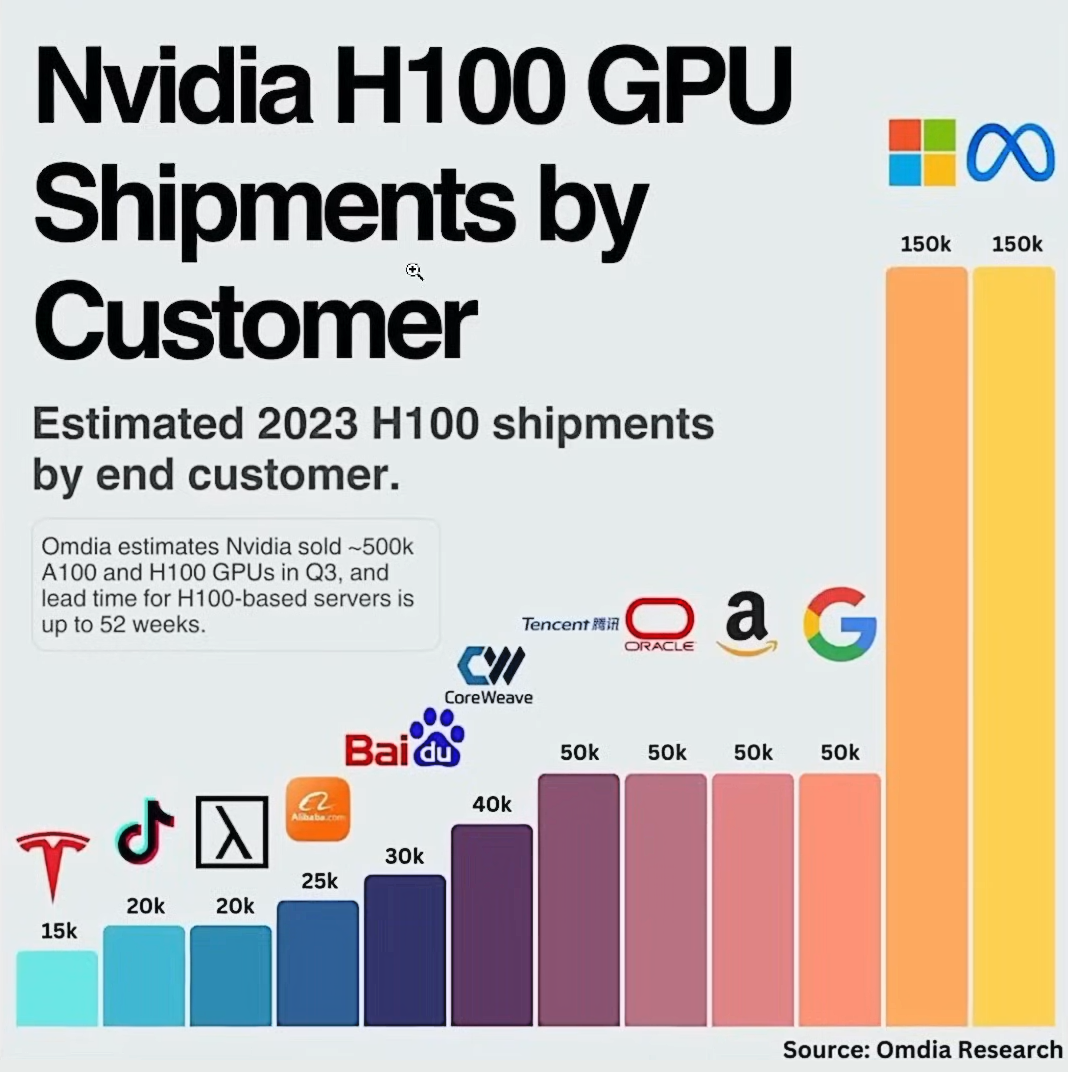

Estimated 2023 H100 shipments by end customer as reported by Omida Research 25.

Contrary to training, the compute for inference has hardly grown in comparison. That is because we want the inference to be fast and cheap in order for it to be practical. There can’t be a seconds of delay for the self-driving car. We don’t want our LLMs to spend hours computing an hour for our question and burn the energy of a small town for it. So with traditional hardware we are quite limited here and models are optimized to work within these boundaries. Imagine what we could do with better dedicated hardware though! Imagine LLMs would respond instantly and run locally on your phone. This will be necessary for robots especially. So while inference does not seem like a growth market at first glance, the demand is absolutely there.

Update: OpenAI released the o1 model recently which uses chain-of-thought self-prompting to deliver higher quality answers at the cost of a longer waiting time and significantly higher token consumption26. A new scaling law was discovered similar to the training scaling laws that shows that the accuracy rises as we spend more time “thinking”. The financial price for using these models is huge. We can therefore expect a much greater demand for better inference. Where I had doubt before if inference hardware made sense, I don’t have this doubt anymore! September 18, 2024

Estimated 2023 H100 shipments by end customer as reported by Omida Research 25.

Contrary to training, the compute for inference has hardly grown in comparison. That is because we want the inference to be fast and cheap in order for it to be practical. There can’t be a seconds of delay for the self-driving car. We don’t want our LLMs to spend hours computing an hour for our question and burn the energy of a small town for it. So with traditional hardware we are quite limited here and models are optimized to work within these boundaries. Imagine what we could do with better dedicated hardware though! Imagine LLMs would respond instantly and run locally on your phone. This will be necessary for robots especially. So while inference does not seem like a growth market at first glance, the demand is absolutely there.

Update: OpenAI released the o1 model recently which uses chain-of-thought self-prompting to deliver higher quality answers at the cost of a longer waiting time and significantly higher token consumption26. A new scaling law was discovered similar to the training scaling laws that shows that the accuracy rises as we spend more time “thinking”. The financial price for using these models is huge. We can therefore expect a much greater demand for better inference. Where I had doubt before if inference hardware made sense, I don’t have this doubt anymore! September 18, 2024

Applications

A figure from the paper showing how much it currently costs even to do just inference. A. S. Luccioni et al. recently compared several machine learning tasks in terms of their energy consumption and nicely showed that image generation is orders of magnitudes more costly during inference compared to other ML tasks like image classification or text generation27:

| Task | Inference Energy (kWh) |

|---|---|

| Text Classification | 0.002 \(\pm\) 0.001 |

| Extractive QA | 0.003 \(\pm\) 0.001 |

| Masked Language Modeling | 0.003 \(\pm\) 0.001 |

| Toke Classification | 0.004 \(\pm\) 0.002 |

| Image Classification | 0.007 \(\pm\) 0.001 |

| Object Detection | 0.04 \(\pm\) 0.02 |

| Text Generation | 0.05 \(\pm\) 0.03 |

| Summarization | 0.49 \(\pm\) 0.01 |

| Image Captioning | 0.63 \(\pm\) 0.02 |

| Image Generation | 2.9 \(\pm\) 3.3 |

Compute / Energy: Human vs. GPT4

At this point, I want to highlight the title figure at the beginning of these notes showing the speed in GOP/s over power in W of GPUs, FPGAs, digital and mixed signal ASICs. More than any other figure here, I think it gives a sense of how the different hardware compares.

I hope to soon go more into depth discussing limits like Landauer’s principle28 as it relates to this. The sad truth as of now is that there seems to be a hard limit for the amount of compute per second we can achieve for the energy used. To drive down the costs or AI developement and inference, we’d have to dramatically reduce the cost of energy, which would require an energy revolution in of itself, or rethink and rebuild our hardware on a much more fundamental level than is currently done (in the industry). That is precisely why I am writing these notes.

Comparisons to the human brain and how it developed are often made, especially now in context of LLMs and their extreme popularity and energy consumption because it requires historic energy consumption to train useful LLMs. Even if we compare all the energy consumed by a human throughout their entire life, the difference is vast. Some napkin math:

Assuming that the calorie intake is 2000 kcal / day \(\times\) 365 days where 1163 Wh = 1000 kcal2930, that’s 730.000 kcal / year or \(8.5 \cdot 10^{-5}\) GWh/year per person. Now multiply this times the decades humans take to learn what LLMs know and we can maybe subtract or or two orders of magnitude in energy consumption. Still, in comparison, OpenAI used 50 GWh to train GPT431utilizing 25.000 NVIDIA A100 GPUs that run around 6.5 kW each. It doesn’t take a math genius to see that there are orders of magnitude in difference. And as a result, the training cost for GPT4 was around $100.000.000 over a period of around 100 days (roughly $65M for the pre-training alone) as stated Sam Altman himself3233.

General Use of Hardware

GPUs: NVIDIA Leads the Way

NVIDIA is the non-plus ultra for AI training at the largest scale. We see this reflected with commercial GPUs providing the fastest training. The drawback: These GPUs also consume by far the most power.

In NVIDIA’s most recent developer conference, Jensen Huang bragged about how hot these GPUs get. So hot, that they need to be liquid cooled (which poses new challenges in data centres). So hot, that the coolant coming out after just seconds could be used as a whirlpool, I remember him stating. Later on stage, he then continued talking about how NVIDIAs new accelerators are now much more energy efficient34. It takes a special kind of genius to pull of such contradiction marketing. I am not even trying to be critical. It’s rather humorous!

Even with their incredible energy demands and the high training costs that follow, NVIDIAs glowing hot GPUs have a bright future.

That is because GPUs offer versatility and power for a wide range of applications. GPUs excel in scenarios where the workload is diverse or evolving, as they are capable of handling various computational tasks beyond AI, including graphics rendering, scientific simulations, and data analytics, all of which can compliment each other. They are the research plattform. Additionally ,they are simply extremely widespread. Nearly every computer has a GPU. Many have NVIDIA GPUs. And NVIDIA made sure to build the entire stack from the bottom up to the higher software layers to make it as easy for developers and scientists to get as much performance without needing to write much code.

Field-Programmable Gate Arrays (FPGAs) for Prototyping

If we were to compete, lowering energy consumption is the angle of attack. FPGAs are, in part, competitive enough in terms of speed yet at similar power consumption and much, much worse usability. Nonetheless, some argue for a future of FPGAs:

“Due to their software-defined nature, FPGAs offer easier design flows and shorter time to market accelerators than an application-specific integrated circuit (ASIC).”35

The advantage lies for tasks that require less compute but desire better optimization in speed and energy efficiency hence inference. And FPGAs are typically easier to bring to market than ASICs. So in scenarios where power consumption must be tightly controlled, such as in embedded systems or edge computing devices, FPGAs may provide a compelling solution. But compelling enough?

Application-Specific Integrated Circuits (ASICs) for on the Edge Devices

ASICs after all are by far superior for addressing energy concerns in AI hardware. Unlike general-purpose GPUs, ASICs are tailored specifically for certain tasks, maximizing efficiency and performance for those tasks while minimizing power consumption. On the other hand, ASICs entail higher initial development costs and longer time-to-market. Since progress in AI is driven primarily by new developments in software, developing ASICs that are general enough to keep up with that progress but specific enough to actually have an advantage over GPUs is tricky.

Tensor Processing Units (TPUs) for Deep Learning Training

Developed by Google, TPUs are designed specifically for accelerating machine learning workloads, particularly those that involve neural network inference and training by focusing on matrix multiplication operations fundamental to neural network computations. And by doing so, TPUs are able to achieve remarkable speedups while consuming significantly less power compared to traditional GPU-based solutions. As I see it, they are simply not as widely available and their lack of generality compared to GPUs may make the development of AI applications a bit more difficult compared to GPUs once again.

Neural Processing Units (NPUs) for Inference

Similarly, NPUs represent a specialized class of AI hardware optimized specifically for neural network computations. They are designed to accelerate the execution of machine learning workloads but, and this is the crucial difference, with a focus on inference tasks commonly found in applications such as computer vision, natural language processing, and speech recognition. By incorporating dedicated hardware accelerators for key operations involved in neural network inference, such as convolutions and matrix multiplications, NPUs are able to achieve significant speedups while consuming less power. So the idea is similar to TPUs but with a focus more on inference specifically for edge devices and private computers.

Conclusion

What I and others ask is what is the computer of the future? I started writing this down because there are so many approaches to AI accelerators. Most quite traditional, simply designing digital ASICs. Some more exotic. Yet they are all extremely confident in that their approach is what the future AI super-computer will look like. That is why one of my I will now be more focused on the physics of computing. I’ll try and look at it from a first-principles standpoint, look at where our corrent technological limitations and lie to then give my personal estimate on what is the most sensible solution we should be working on.

Thank you for reading these notes of mine as I tried to clear up my thinking on the subject. In the end, it lead me to the believe that it is rather pointless to try and directly compare all the available hardware. There are too many nuances and the technical details matter a lot. Yet, it is unclear how and what exactly matters and will be the most important metric to focus on for future computers. It seems to be quite clear to me that current computer designs are primarily driven by the econonmy and not a long-term focus and reasoning from first principles. So I hope to do a better job and illuminate this subject a bit more in a future post that takes a more physics oriented approach. Another lesson I took away for my own work and design process is that I need to iterate faster so I can prove my designs wrong faster as well.

- Quentin

-

https://arxiv.org/pdf/2311.02462.pdf ↩

-

P. Ruch et al., Toward five-dimensionalscaling: How densityimproves efficiency infuture computers, IBM, 2011 ↩

-

Adapted based on a figure originally linked to https://NICSEFC.EE.TSINGHUA.EDU.CN. Yet, I was not able to find it again as the link seemed to have been broken. ↩

-

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2020%E2%80%932023_global_chip_shortage ↩

-

https://edition.cnn.com/2023/08/06/tech/ai-chips-supply-chain/index.html ↩

-

Interview with Elon Musk on X.com: https://twitter.com/i/spaces/1YqJDgRydwaGV/peek Musk mentioned the various bottlenecks of AI in other recent interviews as well. ↩

-

https://finance.yahoo.com/news/electrical-transformers-could-giant-bottleneck-220423599.html ↩

-

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Data_center ↩

-

https://www.olsun.com/power-integrator-data-center-2/ ↩

-

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Von_Neumann_architecture ↩

-

https://www.educatingsilicon.com/2024/05/09/how-much-llm-training-data-is-there-in-the-limit/ ↩

-

Alan Kay, Creative Think, 1982 ↩

-

Harrison Kinsley on X.com: https://x.com/Sentdex/status/1773358212403654860?s=20 ↩

-

Sam Altman on the Lex Fridman podcast: https://lexfridman.com/sam-altman-2-transcript/ ↩

-

Wikipedia: Floating Point Operations Per Second, https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Floating_Point_Operations_Per_Second ↩

-

J. Hestness et al., DEEPLEARNING SCALING IS PREDICTABLE, EMPIRICALLY, https://arxiv.org/pdf/1712.00409.pdf?source=content_type%3Areact%7Cfirst_level_url%3Aarticle%7Csection%3Amain_content%7Cbutton%3Abody_link, 2017 ↩

-

J. Kaplan et al., Scaling Laws for Neural Language Models, ArXiv, 2020: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2001.08361.pdf ↩

-

Gwern actually wrote about the scaling hypothesis on his blog as well: https://gwern.net/scaling-hypothesis ↩

-

Sevilla et al., Compute Trends Across Three Eras of Machine Learning, ArXiv, 2022 ↩

-

Epoch AI, Compute Trends, https://epochai.org/blog/compute-trends ↩

-

Geoffrey Hinton on Twitter in 2020: https://twitter.com/geoffreyhinton/status/1270814602931187715 ↩

-

OpenAI, AI and compute: https://openai.com/research/ai-and-compute ↩

-

https://www.eetasia.com/ai-chip-market-to-reach-70b-by-2026/ ↩

-

George Hotz, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iXupOjSZu1Y ↩

-

Omida Research. (I was unable to find the original source though similar data can be found here: https://www.tomshardware.com/tech-industry/nvidia-ai-and-hpc-gpu-sales-reportedly-approached-half-a-million-units-in-q3-thanks-to-meta-facebook) ↩

-

https://openai.com/o1/ ↩

-

Luccioni et al., Power Hungry Processing: Watts Driving the Cost of AI Deployment?, ArXiv, 2023 ↩

-

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Landauer%27s_principle ↩

-

Feel free to convert back and forth between kcal and Wh yourself at https://convertlive.com/u/convert/kilocalories-per-hour/to/watts#2000. ↩

-

https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kalorie ↩

-

https://www.ri.se/en/news/blog/generative-ai-does-not-run-on-thin-air ↩

-

Knight, Will. “OpenAI’s CEO Says the Age of Giant AI Models Is Already Over”. Wired. Archived from the original on April 18, 2023. Retrieved April 18, 2023 – via www.wired.com. https://www.wired.com/story/openai-ceo-sam-altman-the-age-of-giant-ai-models-is-already-over/ ↩

-

https://patmcguinness.substack.com/p/gpt-4-details-revealed ↩

-

NVIDIA GTC March 2024 Keynote with Jensen Huang: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Y2F8yisiS6E&list=PLZHnYvH1qtOYPPHRaHf9yPQkIcGpIUpdL ↩

-

https://www.allaboutcircuits.com/news/shifting-to-a-field-programable-gate-array-data-center-future/ ↩